Are we on the edge of breaking through, poised to transform how we as humans will make things forever? This CEO thinks so.

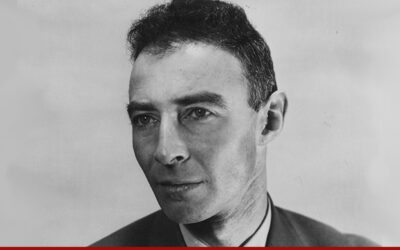

Sonny Vu is used to making big ideas become realities. We met in 2012 when he was launching the MisFit (the name tipped its hat to Apple’s “Think Different” ads back then). It was a simple step-counting/sleep-tracking wearable as elegant and beautiful as it was inexpensive and functional. The company was acquired by Fossil Group for $260 million in 2015.

Vu escaped Vietnam with his family at the height of the Vietnam war, then settled in Oklahoma City. He was six when they arrived, and he grew up “instilled with the immigrant’s dream of a better life,” he says. Since MisFit’s sale, he’s been investing in creating products that have a positive planet-level impact, many of them in the bio-health arena.

Now he’s taken the helm as CEO again, this time at Arevo. Arevo manufactures beautifully-crafted unibody 3D-printed carbon fiber bicycles (pictured at top). The company recently added an elegant lounge chair, Mishima, as its second printed product (at right). But both bike and chair are, in effect, decoys for a grander scheme to use 3D additive manufacturing to build products at scale. Vu’s vision of large 3D-printer farms making the goods we use every day is the big idea behind the company. As he says, “This is a proof of concept for a megatrend that is on the edge of breaking through, poised to transform how we as humans will make things forever.” The end game, he believes, is to be part of a massive shift to manufacturing locally, rapidly, and providing consumers with mass-customization, no longer relying on off-shore manufacturing for parts and consumer products.

3D-printing large items requires a leap of faith compared to the more traditional, less-costly mold-injection processes that typically prevail now for such products. But Vu believes we’ve met a perfect storm. He says that because of “trade wars, fluctuating tariffs and sanctions, supply chain interdependencies being cut, and global shortages of materials, local manufacturing isn’t just a logistical convenience or tax optimization, it’s a matter of supply security.”.

I spoke with Vu at WebSummit in Lisbon, where he iterated the benefits of printing things on demand: “It’s just-in-time manufacturing. You don’t need inventory, because you print orders as they come into the system. And without tooling and molds that need to be re-created each time there’s a product change, you’ve got faster iterations.” One of the biggest strengths of the 3D-printed additive process is that it’s fairly unlimited in terms of the shapes you can design and build, whereas traditional manufacturing is generally limited to more basic shapes.

But the hurdles are formidable. The material costs for additive manufacturing is still almost prohibitively high. And traditional factories that have invested heavily in processes like mold injection are reluctant to change. Finally, the speed and output of a 3D printer compared to an injection mold system is paltry. Here’s a chart that shows the cost of printing a simple bucket using traditional manufacturing processes versus additive manufacturing. It’s pretty daunting.

Today, the Mishima lounge chair sells for upwards of $5,000, and the Superstrata bike, with its unibody carbon-fiber, made-to-order frame is $4,000. Not for the faint of pocketbook.

Other companies attempting to develop 3D printing span a gamut of industries. Relativity Space raised $140 million in financing to make rockets using 3D printers, Velo3D supplies 3D printers for SpaceX to build complex metal engine parts, among other things. Shapeways, one of the pioneers in mass-3D-printer farms, specializes in small-size, low volume objects. Formlabs prints objects using a number of interesting composite resins. ProtoLabs is focused on low-volume product printing, and Desktop Metal also offers 3D products made of carbon fiber. While each has its niche in the engineering world, none have yet to receive the kind of scale or valuation to make them household names. As of today, Arevo has raised northwards of $60 million to expand its manufacturing capabilities.

Finally, there are pros and cons to the sustainability issue, when it comes to additive manufacturing. Carbon fiber printing takes lots of electrical energy, more than traditional manufacturing processes. And recycling carbon fiber is still inefficient. On the flip side, the 3D-printing process generates virtually no waste, and creating customized on-demand products reduces the glut of stuff that floods our markets.

Undaunted, Vu says that additive processes often increase the strength and sturdiness of an item, making it “built to last”. And for now, he expects his customers not to be too price-sensitive, valuing both the strength and beauty of Arevo’s products.

So today you may have learned to imagine computer server farms that mint NFTs or produce Bitcoins. Can you next imagine 3D-printing farms spewing out our personalized products? That’s where Sonny Vu is putting his imagination to work.