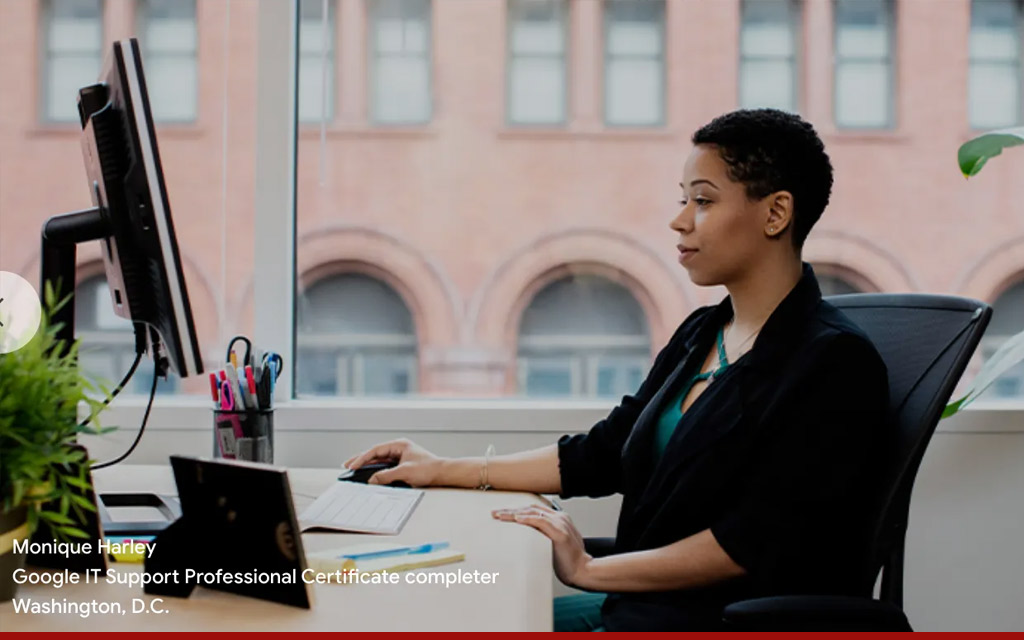

Image via Grow with Google

This week’s Techonomy/CDX/Worth sessions focused on the Health+Wealth of America. So it’s only fitting we look at new research that would paint a rosy picture for tech sector employees, if only educational institutions could fill the pipeline with work-ready students. The study was conducted by the CTA, where my company Living in Digital Times has been a longtime partner.

The jobs are there, but the requisite skills are not. That’s the takeaway from the Consumer Technology Association’s (CTA) latest Future of Work study. In a survey of 240 member companies of all sizes, it found that three in four tech companies face difficulty finding candidates with the right skills and abilities. The CTA expects the need for skilled workers to grow even greater over the coming five years.

Of the employers who took the survey, 57% reported they needed to fill jobs in data analytics, 56% in software development, and 56% in project management. “As they look to fill the gap created by the lack of qualified employees,” Jacqueline Black, director of strategic alliances, U.S. Jobs at CTA said, “companies may also look to apprenticeship programs as a proven way to fill vacant positions and prepare workers with in-demand technical skills.”

This is not the first time that businesses and academia find themselves at loggerheads over the recipe for creating a skilled worker. But finally new solutions are being tested more widely, thanks to a pandemic which forced remote learning onto every academic institution, restrictions to HB-1 visas that grant entry to skilled workers from other countries, and the growing demand for technology- savvy workers.

The Pipeline Problem

College enrollment in the US was on the decline even before COVID. And the decline is contrary to the historical pattern, that shows when the economy tanks admissions to degree programs typically rise. Now, without colleges to fill the jobs pipeline (in part due to skyrocketing costs, in part due the lack of physical classrooms), a plethora of alternatives are emerging. These include coding academies, certification programs, entrepreneurship programs, partnerships with industry, and school-to-work focused community colleges.

Programs like the P-Tech Schools in Minnesota are creating direct school-to-work pipelines. Area employers including IBM, the Mayo Clinic, insurance brokerage RPS and others have partnered with high schools to offer programs to prepare tech and medical workers.

Grow with Google is a wildly ambitious program that offers personal career advancements, including certificates in areas like IT Support s, as well as special programs tailored to small businesses, veterans, educators, and others. Grow with Google has trained more than five million Americans on digital skills since its inception in 2017. Google has not been shy in promoting its courses as a low cost, highly targeted ways to land high tech jobs, both at Google and elsewhere.

The initial program certified students for IT Support. Based on that success, the company recently introduced courses in data analytics, programming and user experience design. “We created Grow with Google to solve our own tech hiring issues”, says Jesse Haines, director at Grow with Google. “Now we have 60 companies participating as part of our consortium, so that a student can complete a course and directly enter the job pipeline.

Companies like Trilogy (recently acquired by 2U) offer hundreds of courses across many vertical fields, often white-labeling them for universities. Both Harvard and MIT offer Trilogy-powered certification programs. Their high-status imprimaturs are further legitimizing skills-based learning.

Startups like Guild and InStride work as intermediaries between colleges and employers, creating customized programs to help match skills with jobs. Efforts like these hold great promise, targeted at workplaces that need specifically-skilled labor but cannot afford the costs or distraction of administering their own programs.

I spoke with Michael Goldstein, managing director of strategic advisory and investment firm, Tyton Partners, which focuses heavily on education. He is co-creator of Tyton’s new Center for Higher Education Transformation, and a longtime observer of higher education. Over a Zoom call, he reminded me that the tension between workforce preparedness and academia is nothing new. Goldstein says that this moment is about expectations. “There has long been a disconnect between what constitutes many degree programs and what employers say they want to see in new recruits.” He continued: “Much of that depends on your definition of what is preparedness. And the only way to solve that problem is for there to be far more college-employer collaboration. Without that, turning out graduates who are employable with no further training by the employer seems unrealistic.”

Goldstein said the dearth of skilled candidates is magnified by the current administration’s curtailing of HB-1 visas. Businesses that relied heavily on overseas talent to fill jobs have been left shorthanded while academia struggles with a slowing pipeline of talents.

The CTA’s Future of Work group, responsible for this study, confirms that companies are looking beyond colleges and other traditional hiring pathways. It reports that 58% of the surveyed companies do not require a college degree for open positions (technology based or otherwise). [“With the continued demand for skilled talent,” says CTA’s Jackie Black, “it is critical for employers to look to alternative hiring pipelines, such as apprenticeships. Almost one-quarter (24%) of employers will hire more from train-to-hire programs such as apprenticeships. This does not mean the end for traditional education – and the report even shows that most companies who collaborate with educational institutions do so with four-year universities. But it does mean that we should continue to rethink hiring based on degree requirements and focus on skills-based hiring.”

Says Tyton’s Goldstein: “I am confident that the return to the ‘new normal,’ whenever that occurs, will accelerate the engagement of many institutions in more targeted, career-oriented programs.”

Soft Skills Rising

Lest you think businesses are limiting the work place skills they want solely to technical ones, it’s interesting to note that the CTA also asked respondents to rate the importance of “soft skills”. The findings showed high demand for capabilities like effective communications, problem-solving and critical thinking, with those often ranking even higher than tech skills.

Goldstein is not surprised by this finding: “Companies want ‘trained’ workers, but when they are askedthe answer changes as you go up the food chain. At the CEOs level there ‘s more and more emphasis on soft skills.” Perhaps, he concludes, there is as much tension and confusion about this issue inside companies as between employers and institutions. Here is a question that clarifies the challenge: “Is it easier to teach a philosopher to code, or to teach a coder to philosophize?”

Businesses and educators have always enjoyed a healthy tension over what constitutes job preparedness. Now, a triple cocktail is bringing about swift transformation. First, the pandemic resulted in even the highest echelons of higher ed going online, making the college experience less unique than it had been. Next, we’ve experienced a lack of available overseas talent pool. And finally, we’re seeing a workforce that needs greater technical skills as WFH and a more technical workplace takes shape. Together the cocktail creates vast opportunities for smart educators and smart companies to step up, work to help people, and lessen the friction between schools and business.

READ MORE: https://techonomy.com/2020/10/desperately-seeking-talent-technology-association-report-underscores-shortage-of-skilled-workers/