I’m no longer hiding under my desk awaiting missiles, but don’t be surprised if you see me stockpiling chips in my desk drawer. Many companies have already reported doing the same, many of them Chinese companies.

As an elementary school student during the Kennedy Administration, I recall not infrequently spending a bit of my school day under my desk. Younger readers never had, as we baby boomers did, to “duck and cover,” as a supposed protection against a potential nuclear attack. At some schools, the teacher would, in the middle of a lesson, simply say “Oh-drop!” That meant we should jump underneath our desks. Or sometimes they lined us up in the cinderblock hallway, facing the wall. But that Cold War, real as it was, seems positively quaint now.

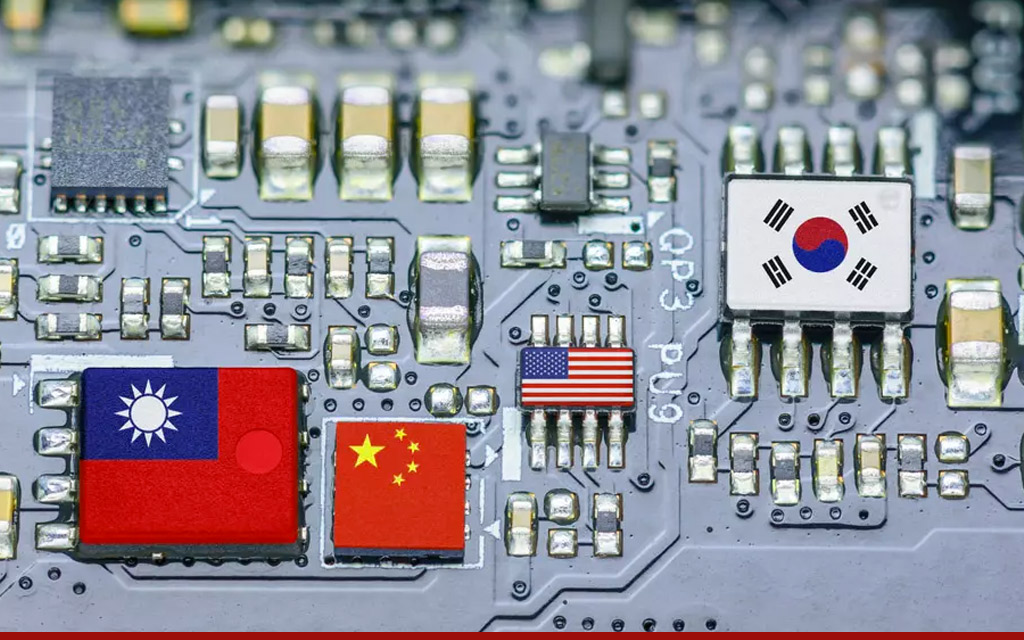

Now the next cold war is unfurling. It is big, complicated, very real, and has massive global repercussions. It’s mostly between China and the U.S. But while the tension between the two nations has many tentacles, an increasingly central role is being played by chips, semiconductors and the machines used to make them..

“We rarely think about chips, “ says Chris Miller in his new book Chip War, “yet they’ve created the modern world.” Chips, he continues “are the new oil.” Marc Andreessen may have famously said, “software will eat the world,” but it’s semiconductors that give it the teeth to do that.

While the Trump administration growled about being tough to keep China from pulling ahead in the chip race, the Biden Administration has gone full bulldog. It now wants to curb China’s ability to create and deploy the next generation of super powerful chips as much as possible. The results of this effort are confusing, far reaching and global.

Will the U.S. consumer eventually have to start stockpiling digital devices, fearful of a worldwide chip shortage? How much have the Chinese, led by their consummately tech-savvy government, already stockpiled? Can the U.S. really build its own semiconductor fabrication plants fast enough to meet the growing need for onshore assets? (The Biden Administration impressively enacted the expensive Chips Act over the summer to hasten research and production efforts for new generation chip research and fabrication. But one chip fab costs in the vicinity of $20 billion dollars to build, a process that takes quite a few years.) What does it mean that the world’s most advanced chip plants are only a few hundred miles from the shores of China, in Taiwan, and that Xi Jinping repeatedly makes it seem like China might invade Taiwan?

The Back Story

On Oct 7th, the Biden Administration dramatically ratcheted up its efforts to curb China’s domination of the chip industry, by placing stringent new restrictions on selling semiconductors and chip-making equipment to China, and on how individual Americans could work with the Chinese chip industry. The new rules forbid American companies from exporting the advanced chips China needs to train and run the most powerful AI software. (Keep in mind that right now in many ways China leads the world on AI, and has placed huge priority on continuing to develop it for all sorts of domestic and political and intelligence reasons.) The aim is to curtail China’s ambitions to develop its own cutting-edge semiconductor industry. And we’re not talking about “some time in the near future”. These restrictions begin almost immediately–October 21st.

Instead of targeting specific Chinese companies such as Huawei, as the U.S. government did in the past, the new restrictions require U.S. companies to secure licenses from the Department of Commerce before they can export certain chips used in artificial intelligence and supercomputing, as well as equipment used in advanced semiconductor manufacturing. The ban is not outright, but U.S. companies must stop supplying Chinese chipmakers with the necessary equipment to produce advanced chips unless they first obtain a license from the Department of Commerce. The restrictions also block the export of chips or chip making equipment from world leaders in semiconductors including Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung, because all of them incorporate, to some degree, technology developed by American companies.

Simultaneously, in an attempt to further choke Chinese ambitions, new rules restrict U.S. experts who work for Chinese semiconductor industries. The rules instructed all Americans working for Chinese semiconductor companies to stop or face uncertain serious penalties. The rules even apply to holders of American green cards and American residents. According to the WSJ, at least 43 senior executives working with 16 publicly listed Chinese semiconductor companies are American citizens, many of them with C-suite titles, from chief executive. Here’s a note that went out from ASML, a semiconductor company based in the Netherlands with numerous employees in China. (ASML’s latest technology is indispensable for the fabrication of any state-of-the-art chip.)

Taiwan in the Middle

From a geopolitical perspective, in the middle of the China/U.S. powerplay lies Taiwan. China wants it reunified with the mainland and the U.S. wants it to remain an independent democracy. It is the largest creator of high end semiconductors, and world-leading chipmaker TSMC it’s behemoth.

“If Taiwan chipmaking were to be knocked offline, there wouldn’t be enough capacity anywhere else in the world to make up for the loss,” explains Chris Miller, an international history professor at Tufts and the author of Chip War in this article in VOX. “Even simple chips will become difficult to access, just because our demand outstrips supply.” Perhaps Taiwan is guaranteeing its independence from China in part by being such a critical U.S. supplier of these foundational components for modern life.

For the past decade, says Miller, China has spent more money importing chips than importing oil, because it has been unable to produce advanced chips at home like those in phones, PCs, and servers. China relies almost exclusively on foreign firms for the most advanced processor and memory chips.

Outside of Intel all the leading edge chip making today is very close to China – TSMC in Taiwan or Samsung in South Korea). U.S. companies like AMD, Apple and NVIDIA, are all designing powerful new chips, but remember they don’t actually manufacture them (they are all made by TSMC in Taiwan). From a geopolitical standpoint he reiterated, if something happened to Taiwan today, there simply wouldn’t be many tech products left.

Meanwhile, China has in fact been making steady progress towards producing high-end chips within the country as this chart from SEMI indicates.

However, China’s leading domestic chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), still produces chips that lag several generations behind those of TSMC, Samsung, and Intel, according to this piece in Wired.

Concludes the Council on Foreign Relations: “The new restrictions are seen as a strategy to freeze China at a backward state of semiconductor development and cut Chinese companies off from U.S. industry expertise.”.

Not So Fast

But don’t fly any victory flags. Intel, after promising to build new fab labs in part to take advantage of American Chips Act largesse, is laying off staff. The China-U.S. AI research gap continues to widen, with Chinese institutions producing 4.5 times as many papers as American institutions since 2010. Chinese researchers generate significantly more such work than do the U.S., India, the UK, and Germany combined.

Moreover, China significantly leads in areas with implications for security and geopolitics, like software for surveillance, autonomy, scene understanding, and object detection. Two sobering charts from the Center for Strategic International Studies help tell the story.

I’m no longer hiding under my desk expecting missiles, but don’t be surprised if you see me stockpiling chips in my desk drawer. Many companies at least are already doing that, many of them Chinese.

Extra Credit: Read Chris Miller’s The Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, just published. It traces the history of the chip industry through economic, technical and geopolitical lenses.

Source: https://techonomy.com/the-next-cold-war-has-a-chip-in-it/